Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Diagnosed

How Is Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Diagnosed?

If there is a reason to suspect you may have lung cancer, your doctor will use one or more methods to find out if the disease is really present. In addition, a biopsy of the lung tissue can confirm the diagnosis of cancer and also give valuable information that will help in making treatment decisions. If these tests find lung cancer, more tests will be done to find out how far the cancer has spread.

Common Signs and Symptoms of Lung Cancer

Although most lung cancers do not cause any symptoms until they have spread too far to be cured, symptoms do occur in some people with early lung cancer. If you go to your doctor when you first notice symptoms, your cancer might be diagnosed and treated while it is in a curable stage. Or, at the least, you could live longer with a better quality of life. The most common symptoms of lung cancer are:

- a cough that does not go away

- chest pain, often aggravated by deep breathing, coughing and even laughing

- hoarseness

- weight loss and loss of appetite

- bloody or rust-colored sputum (spit or phlegm)

- shortness of breath

- recurring infections such as bronchitis and pneumonia

- new onset of wheezing

When lung cancer spreads to distant organs, it may cause:

- bone pain

- neurologic changes (such as headache, weakness or numbness of a limb, dizziness, or recent onset of a seizure)

- jaundice (yellow coloring of the skin and eyes)

- masses near the surface of the body, due to cancer spreading to the skin or to lymph nodes {collection of immune system cells) in the neck or above the collarbone

If you have any of these problems, see your doctor right away. These symptoms could be the first warning of a lung cancer. Many of these symptoms can also result from other causes or from noncancerous diseases of the lungs, heart, and other organs. Seeing a doctor is the only way to find out. Other symptoms are listed below.

Horner syndrome: Cancer of the upper part of the lungs may damage a nerve that passes from the upper chest into your neck. Doctors sometimes call these cancers Pancoast tumors. Their most common symptom is severe shoulder pain. Sometimes they also cause Horner syndrome. Horner syndrome is the medical name for the group of symptoms consisting of drooping or weakness of one eyelid, reduced or absent perspiration on the same side of your face and a smaller pupil (dark part in the center of the eye) on that side.

Paraneoplastic syndromes: Some lung cancers may produce hormone-like or other substances that enter the bloodstream and cause problems with distant tissues and organs, even though the cancer has not spread to those tissues or organs. These problems are called paraneoplastic (Latin for “tumor-related”) syndromes. Sometimes these syndromes may be the first symptoms of early lung cancer. Because the symptoms affect other organs, patients and their doctors may suspect at first that diseases other than lung cancer cause them.

The most common paraneoplastic syndromes caused by non-small cell lung cancer are:

- Hypercalcemia (high blood calcium levels), causing urinary

- frequency, constipation, weakness, dizziness, confusion, and other nervous system problems

- Excess growth (sometimes painful) of certain bones, especially those in the finger tips. The medical term for this is hypertrophic osteoarthropathy

- Production of substances that activate the clotting system, leading to blood clots.

- Excess breast growth in men. The medical term for this condition is gynecomastia

Medical History and Physical Exam

Your doctor will take a medical history (health-related interview) to check for risk factors and symptoms. Your doctor will also examine you to look for signs of lung cancer and other health problems.

Imaging Tests

Imaging tests use x-rays, magnetic fields, or radioactive substances to create pictures of the inside of your body. Several imaging tests are used to find lung cancer and determine where it may have spread in the body.

Chest x-ray: This is the first test your doctor will order to look for any mass or spot on the lungs. It is a plain x-ray of your chest and can be done in any outpatient setting. If the x-ray is normal, you probably don’t have lung cancer. If something suspicious is seen, your doctor may order additional tests

Computed tomography (CT): The CT scan is an x-ray procedure that produces detailed cross-sectional images of your body. Instead of taking one picture, as does a conventional x-ray, a CT scanner takes many pictures as it rotates around you. A computer then combines these pictures into an image of a slice of your body. The machine will take pictures of multiple slices of the part of your body that is being studied. Often after the first set of pictures is taken you will receive an intravenous injection of a “dye” or radiocontrast agent that helps better outline structures in your body. A second set of pictures is then taken.

CT scans take longer than regular x-rays and you will need to lie still on a table while they are being done. But just like other computerized devices, they are getting faster and your stay might be pleasantly short. The newest CT scans take only seconds to complete. Also, you might feel a bit confined by the ring-like equipment you’re in when the pictures are being taken.

The contrast “dye” is injected through an IV line. Some people are allergic to the dye and get hives, a flushed feeling, or rarely more serious reactions like trouble breathing and low blood pressure. Be sure to tell your doctor if you have ever had a reaction to any contrast material used for x-rays. If you have, you may need medicine before you can have such an injection during your test.

You may also be asked to drink a contrast solution. This helps outline your intestine if your doctor is looking at organs in your abdomen to see if the lung cancer has spread.

The CT scan will provide precise information about the size, shape, and position of a tumor and can help find enlarged lymph nodes that might contain cancer that has spread from the lung. CT scans are more sensitive than a routine chest x-ray in finding early lung cancers. This test is also used to find masses in the adrenal glands, brain, and other internal organs that may be affected by the spread of lung cancer.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): MRI scans use radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays. The energy from the radio waves is absorbed and then released in a pattern formed by the type of tissue and by certain diseases. A computer translates the pattern of radio waves given off by the tissues into a very detailed image of parts of the body. Not only does this produce cross sectional slices of the body like a CT scanner, it can also produce slices that are parallel with the length of your body.

A contrast material might be injected just as with CT scans, but is used less often. MRI scans take longer – often up to an hour. Also, you have to be placed inside a tube-like piece of equipment, which is confining and can upset people with claustrophobia. The machine makes a thumping noise that you may find annoying. Some places will provide headphones with music to block this out. MRI images are particularly useful in detecting lung cancer that has spread to the brain or spinal cord.

Positron emission tomography (PET): Positron emission tomography (PET) uses glucose (a form of sugar) that contains a radioactive atom. Cancer cells in the body absorb large amounts of the radioactive sugar and a special camera can detect the radioactivity. This can be a very important test if you have early stage lung cancer. Your doctor will often use this test to see if the cancer has spread to lymph nodes. It is also helpful in telling whether a shadow on your chest x-ray is cancer. PET scans are also useful when your doctor thinks the cancer has spread, but doesn’t know where. PET scans can be used instead of several different x-rays because they scan your whole body. Newer devices combine a CT scan and a PET scan to even better pinpoint the tumor.

Bone scan: In a bone scan, a small amount of radioactive substance (usually technetium diphosphonate) is injected into a vein. The amount of radioactivity used is very low and causes no long-term effects. This substance builds up in areas of bone that may be abnormal because of cancer metastasis. However, other bone diseases can also cause cause abnormal bone scan results. Bone scans are only done in patients with non-small cell lung cancer when other test results or symptoms suggest that the cancer has spread to the bones.

Procedures that Sample Tissues and Cells

One or more of these tests will be used to confirm that a lung mass seen on imaging tests is a lung cancer, rather than a benign condition. These tests are also used to determine the exact type of lung cancer you may have and to help determine how far it may have spread.

Sputum cytology: A sample of phlegm (the best way is to get early morning samples from you 3 days in a row) is examined under a microscope to see if cancer cells are present.

Needle biopsy: After numbing the skin with local anesthesia, a doctor can direct a needle into the mass while looking at your lungs with fluoroscopy (fluoroscopy is like an x-ray, but the image is shown on a screen rather than on film). CT scans can also be used to guide the placement of needles. Unlike fluoroscopy, CT doesn’t provide a continuous picture so the needle is inserted in the direction of the mass, a CT image is taken, and the direction of the needle is guided based on the image. This process is repeated a few times until the CT image confirms that the needle is within the mass. A tiny sample of the tumor is sucked into a syringe and examined under the microscope to see if cancer cells are present. One possible complication of this procedure is that air may leak out of the lung at the biopsy site. This can cause the lung to collapse and cause trouble breathing. It is treated by putting a small tube into the chest space and sucking out the air over a day or two.

Bronchoscopy: You will need to be sedated for this exam. A fiberoptic flexible, lighted tube is passed through your mouth into the bronchi (the larger tubes which carry air to the lungs). This can help find some tumors or blockages in the lungs. At the same time, it can also be used to take biopsies (samples of tissue) or samples of lung secretions to be examined under a microscope for cancer cells or precancerous cells. Studies are being done to see if annual exams will be helpful in finding premalignant changes in people at high risk.

Endobronchial ultrasound: In this technique the bronchoscopy tube is fitted with an ultrasound emitter and receiver at its tip. This may be helpful in gauging the size of the tumor and in spotting enlarged lymph nodes. A fine needle passed through the biopsy channel can sample these nodes under ultrasound guidance.

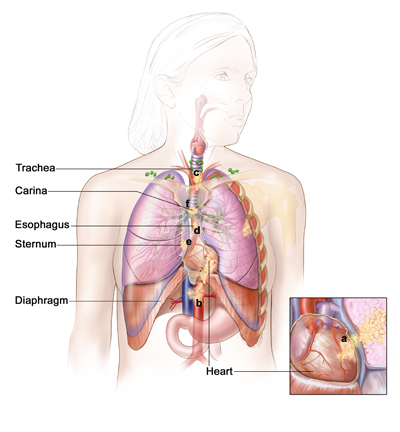

Endoscopic esophageal ultrasound (EUS): In this technique a flexible fiberoptic scope is fitted with an ultrasound emitter and receiver at its tip and passed into the esophagus. This is done with light sedation. The esophagus is close to some lymph nodes inside the chest, and lung cancer can spread to these lymph nodes. Ultrasound images taken from inside the esophagus can be helpful in finding large lymph nodes inside the chest that might contain metastatic lung cancer. A fine needle passed through the biopsy channel can sample these nodes under ultrasound guidance.

Mediastinoscopy and mediastinotomy: For both of these procedures, you will receive general anesthesia (be put into a deep sleep). With mediastinoscopy a small cut is made in your neck and a hollow lighted tube is inserted behind the sternum (breastbone). Special instruments, operated through this tube, can be used to take a tissue sample from the mediastinal lymph nodes (along the windpipe and the major bronchial tube areas). Looking at the samples under a microscope can show whether cancer cells are present.

Mediastinotorny also removes samples of mediastinal lymph nodes while the patient is under general anesthesia. Unlike mediastinoscopy, the surgeon opens the chest cavity by making a small incision beside the sternum. This allows the surgeon to reach lymph nodes that are not reached by standard mediastinoscopy.

Thoracentesis and thoracoscopy: These procedures are done to find out whether or not a build-up of fluid around the lungs (pleural effusion) is the result of cancer spreading to the membranes that cover the lungs (pleura). The build-up might also be caused by a condition such as heart failure or an infection. For thoracentesis, the skin is numbed and a needle is placed between the ribs to drain the fluid. The fluid is checked under a microscope to look for cancer cells.

Chemical tests of the fluid are also sometimes useful in distinguishing a malignant pleural effusion from a benign one. Once a malignant pleural fluid has been diagnosed, thoracentesis may be repeated to remove more fluid. Fluid build-up can prevent the lungs from filling with air, so thoracentesis can help the patient breathe better.

Thoracoscopy is a procedure that uses a thin, lighted tube connected to a video camera and monitor to view the space between the lungs and the chest wall. Using this, the doctor can see cancer deposits and remove a small piece of the tissue to be examined under the microscope. Thoracoscopy can also be used to sample lymph nodes and fluid.

Blood counts and blood chemistry: A complete blood count (CBC) determines whether your blood has the correct number of various cell types. For example, it can show if you are anemic. This test will be repeated regularly if you are treated with chemotherapy, because these drugs temporarily affect blood-forming cells of the bone marrow. The blood chemistry tests can spot abnormalities in some of your organs. If cancer has spread to the liver and bones, it may cause certain chemical abnormalities in the blood. If one of these in particular, called the LDH, is elevated, it usually means that the outlook for cure or long-term survival isn’t good.